Data Discounts

Everyday Futures #1

Exploring the potential everyday complexities of receiving discounts in exchange for our personal data.

Throughout history, personal information has strengthened the relationships between businesses and their patrons.

Customers of ‘mom & pop stores’ exchanged information and facilitated relationships through personal interactions with store owners, who gave their most trusted customers leverage and leniency.

While the means of collecting and exchanging this information have come a long way, the general principles of sharing personal information to strengthen a relationship with a business have hardly changed.

Through today’s 24/7 usage of our mobile phones and digital services, we create a wealth of information about our behaviors in all aspects of our lives.

From constantly checking Facebook, emailing our friends, and moving around the city, we record our own behaviors in unprecedented ways.

This data holds wealth not only for the services themselves, but also for the businesses we interact with.

Utilizing our personal data, these businesses can optimize their operations, target their customers with increasingly accurate ads, and give discounts to promising customers.

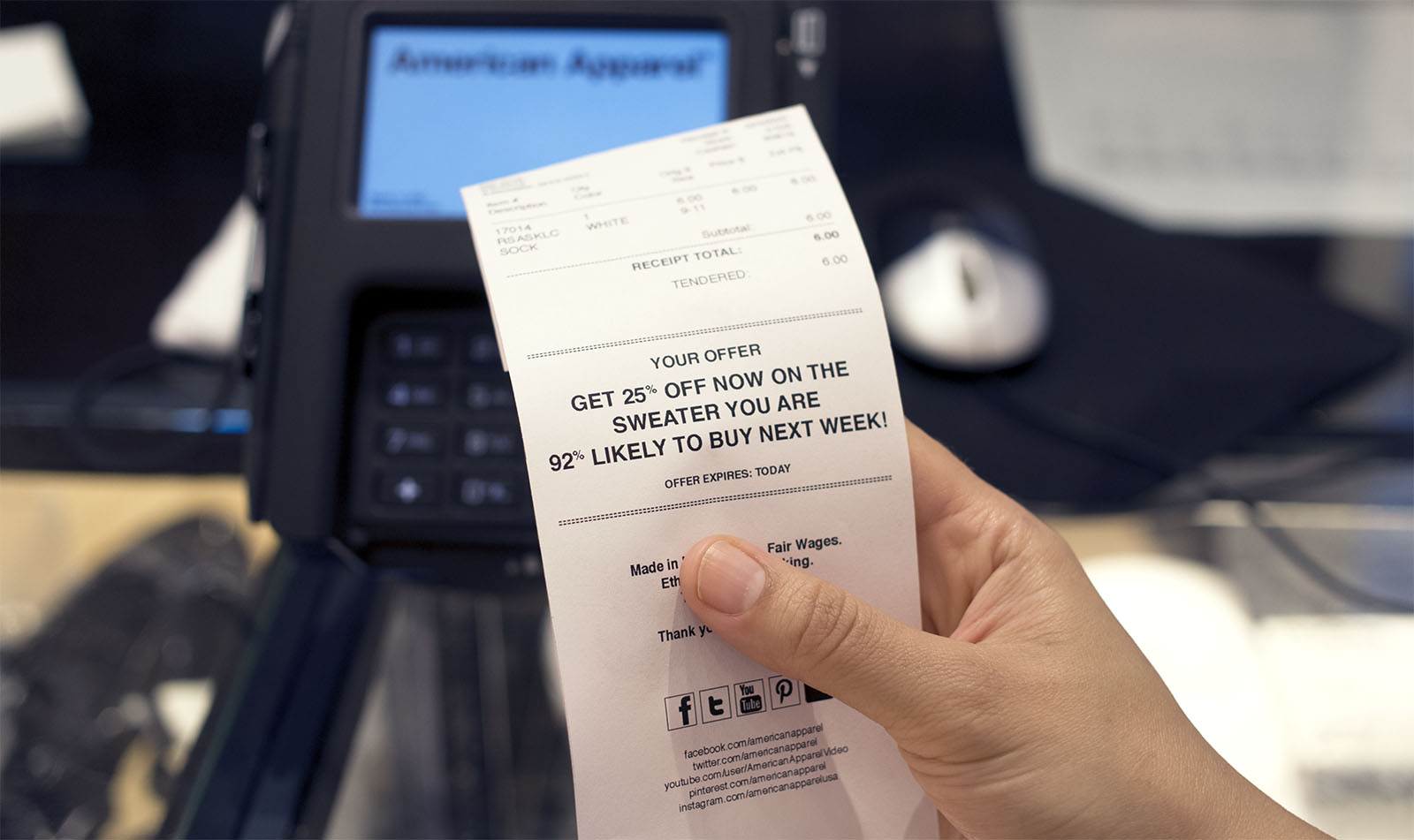

Location Data

Location data collected by the Facebook Moves App

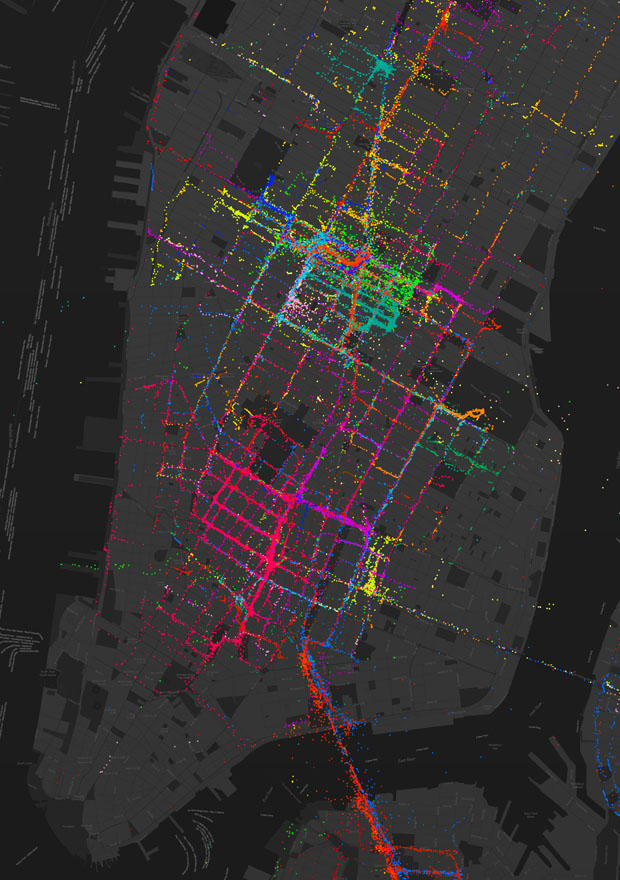

Social Graphs

A social graph derived from LinkedIn data (Image Source: Amber Case / Flickr)

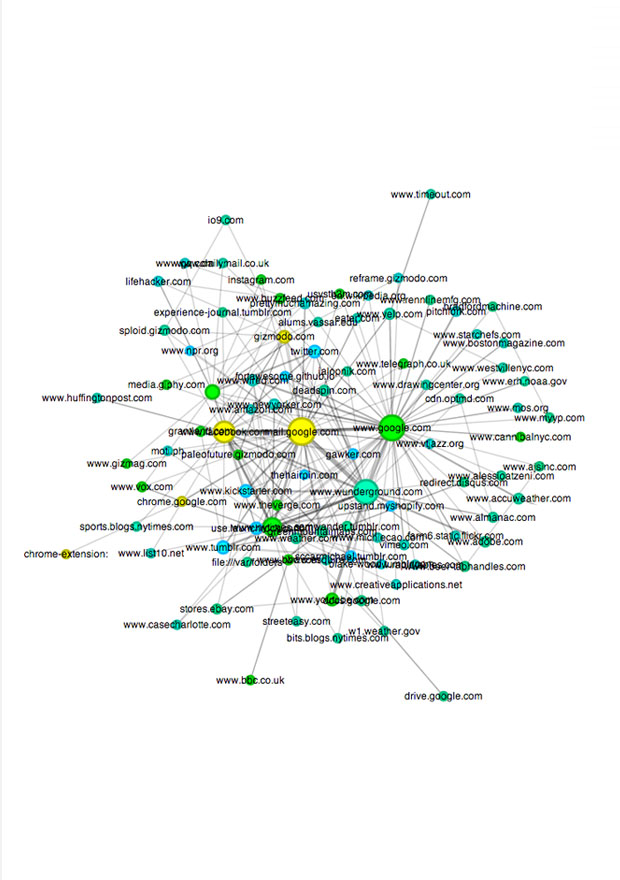

Browsing History

A browsing history visualized with the Google Chrome plug-in ‘Visual History’

Current models around discounts for personal data are still in their infancy due to a variety of issues, ranging from privacy to the difficulty of managing access to personal data, but it is likely that the wealth of our personal data will eventually be utilized to some extent by the businesses we interact with.

Recent examples such as John Hancock Insurance or Russia's Alfa Bank, that already reward healthy behavior with discounts, hint toward a potential everyday reality of discounts and preferential treatment in exchange for access to our personal data trails.

Data Discounts - Soon at a location near you?

If it became commonplace that we would receive discounts in exchange for our personal data from the businesses we interact with, what would be some of the behavioral consequences or social complexities that may arise?

Due to the proliferation of social media in our everyday lives, we are used to liking, retweeting, or reacting to our friends’ posts as well as those of brands and their products.

Fishing for Discounts - Sending out an aggregated personal data snapshot

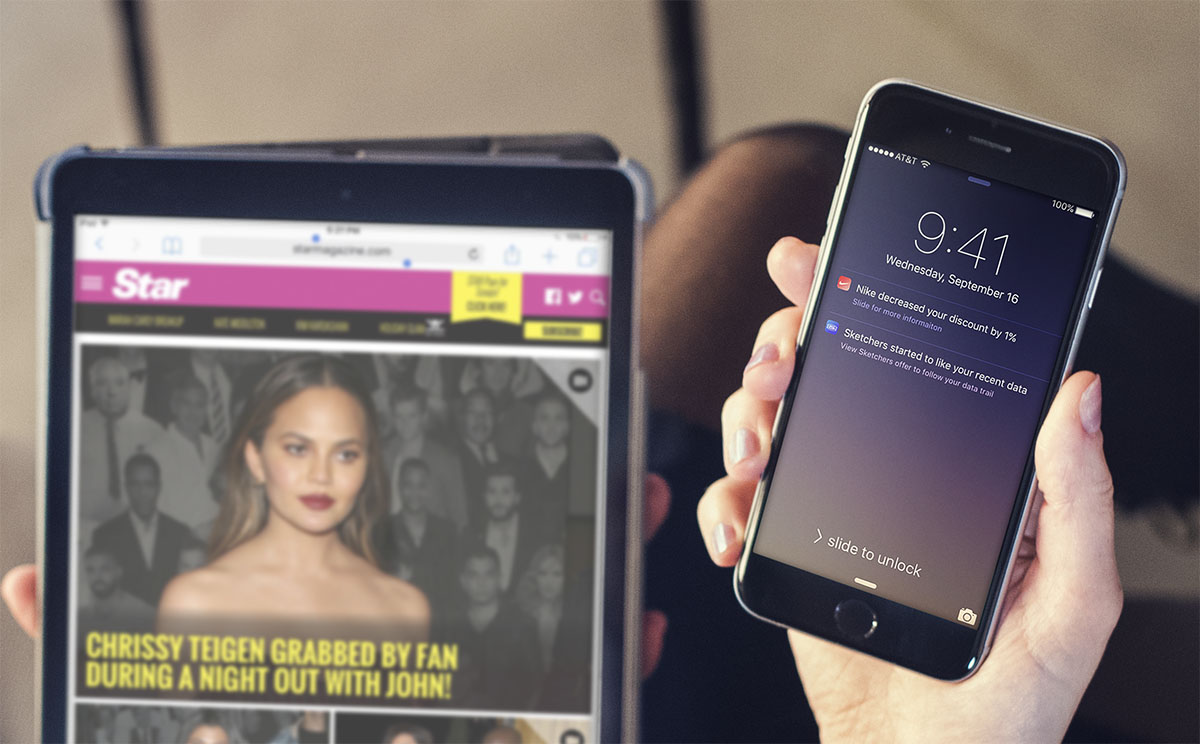

Hooked on our personal data - Brands courting us for our personal data

Imagine the current model of consumers’ liking brands and their ‘data’ in the form of product images on our social media channels but applied in reverse: brands could start to personally ‘like’ us and our data trails, based on small snippets provided through a facilitator, to form highly personal, direct ‘data bonds’ with us and our data.

If, based on a small data snapshot, brands could openly request to follow our data trails in exchange for discounts, what would these new data courtships look like?

Would the perception of our own social positioning—which is partially defined through the brands with which we associate ourselves—match the brands that would become intrigued by our data trails?

Given the complexity of our personal data sources, the question of how and to what extent sufficient control mechanisms will be established is still somewhat unresolved.

Benefit vs. Privacy – How long would we keep our guard up if the perceived benefit is so close to us?

Even if these mechanisms were in place, a missing ‘data literacy’ prevents the end user from understanding exactly what they are giving up with their data and what the potential consequences are of their personal data being ‘out there.’

In addition to this unawareness and the impossibility of understanding the exact consequences of giving up our data, these ‘data permissions’ are yet another thing to control in our already hectic lives.

These factors make this a challenging and still unresolved question.

If mechanisms were in place, though, that would enable us to actively control our data - or at least give us the perception of being in control - at what point would the perceived benefit outweigh our privacy concerns and the often too-abstract-to-understand consequences of giving up parts of our personal data?

Traditionally, the brands we buy, wear, and associate with have been an important definition of our social positioning, presentation to the outside world, and resulting status.

Data Portfolios – New potential data divides between us and our social circles?

From Nike or Apple as desirable and trusted brands to companies like Walmart or Target, our perception of the businesses we interact with runs a wide gamut shaped by a complex interplay of public brand perception, brand influences, our own experiences, and our social circles.

Brands we associate ourselves with can say a lot about our background, friends, and social status.

If our ‘data value’ with the brands we like, shop, and interact with would become openly visible, what would be some of the potential consequences in our social environment?

What new complexities will arise when we are visibly aware of how brands perceive us, our friends, and our everyday behaviors, and what could be some of the potential social consequences of these visibly made ‘data classes’?

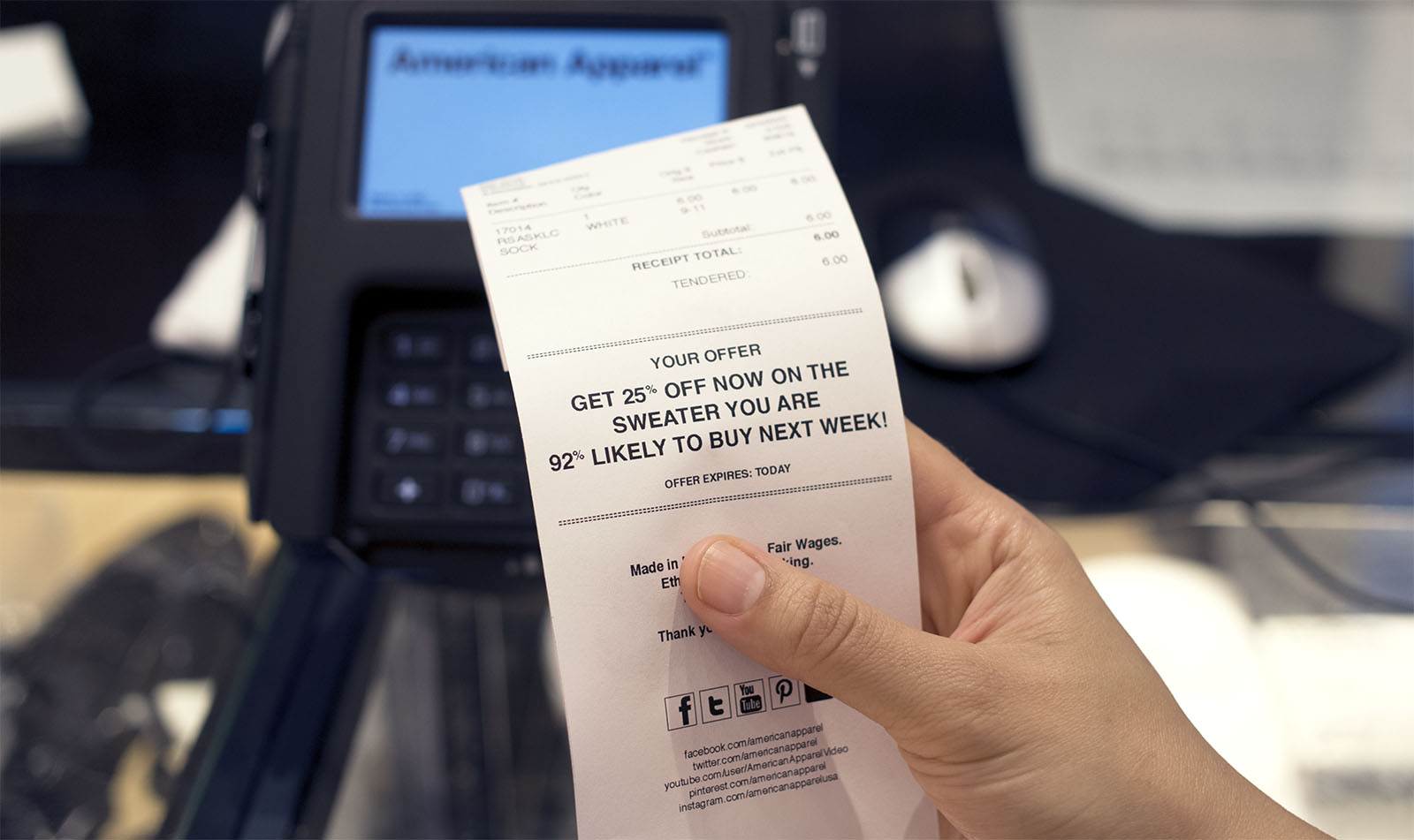

From the coupons on the back of our receipts to referring friends for incentives, we are used to living with discounts in various forms.

Traditional discount systems operate on a 1-to-1 relationship between a brand and their potential customers, usually through offers. The interconnections made possible with our personal data will most likely bring discounting systems to a new level.

New ‘Machine-Man’ Relationships – How deeply engrained would these discounts become in our everyday lives?

It is interesting to imagine which future connections will arise from the possible correlations between currently separate data sources and the prompts that this may bring about if everything becomes trackable and traceable.

It is not too far-fetched to imagine this future in which our social leverage will be utilized by our acting as the messengers delivering the algorithmically created message to bridge the last mile.

If increasingly deep correlations in the data of ourselves and our environments become possible, how invasive would this be, and to what extent would we become part of these processes?

If these discounts and their prompts reach into the nooks and crannies of our everyday lives, what kind of fine lines will we have to navigate between benefit and privacy, and also which behavioral conflicts or moral and ethical dilemmas may we find ourselves in?

Brand perception is not just one-way (consumer to brand). Brands also have a very clear perception of other brands and an understanding of their relative positioning to each other.

New Hidden Complexities – What new ‘data chain reactions’ would be created among our data trail followers?

Clearly outlined guidelines determine which associations with other brands could be detrimental or favorable to their own positioning.

Brand positionings and strategies are determined by a complex system of associations with demographic profiles and a clear differentiation from other brands.

If, by letting brands follow our data trails, our small guilty pleasures would be tracked at any time, what kind of new complexities and ‘data chain reactions’ would this cause among the brands we share our data with?

The ubiquitous use of social media and the deeply ingrained routines of checking our popularity on Instagram or updating ourselves on the latest Twitter following have created a culture that embraces the popularity of being ‘liked’ and being in-demand as never before seen.

Data Trail Unfollowing – How would we react to brands unfollowing our data trails?

We can’t help but check our latest friend requests, monitor our number of Twitter followers, and wonder why our latest Instagram post hasn’t received the expected number of likes.

As with our current social media apps, in an everyday future where brands may directly follow our personal data trails, we will be made aware of the immediate change in our following or consequences of our actions as they happen.

If the liking of us and our data trails became our everyday norm, what would our reactions be to brands visibly losing interest in—or even unfollowing—our data trails?

To what extent would we alter or change our behaviors if we were continuously made aware of brands’ perceptions of ourselves and our behaviors?

Current discussions around small and big data tend to be based on the assumption that our western, affluent state of technology is the ubiquitous status quo that we design to.

Sorry, No Discount Possible – A new reality of data divides?

Discussions tend to be centered around privacy issues, with little focus on the ‘risks of exclusion’ and the ‘data-have-nots’ who interact on the periphery of the data revolution, without a ‘sufficient’ data trail, or whose behaviors are not yet tracked, traced, and analyzed.

If the systems we design and put in place are based on this status quo, their modus operandi will likely neglect the slices of society that are not yet part of our data economy.

If the assumptions when designing these systems are based on our affluent, western technological reality as the status quo, what will happen to the people who interact at the margins of our 24/7 data collection mechanisms?

While there are clearly benefits to collecting our personal data, there will also be cultural issues and complexities that we will have to navigate when designing systems that make use of our personal data trails.

Everyday Futures #1 – Data Discounts explores some of the everyday complexities of receiving discounts in exchange for our personal data.

Everyday Futures is a ongoing series by Daniel Goddemeyer / OFFC that explores the potential cultural implications of today’s emerging technologies becoming tomorrow’s everyday reality.